IMAGE: Georgetown's Patrick Ewing shoots against UNC in the 1982 National Championship game. (NCAA Photos/Getty)

I recently finished reading When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing, written by Daniel H. Pink, which explores how “good” timing can help us to succeed in both our personal and professional lives.

In one chapter Pink discusses the midpoint, and how things can go one of two ways when we reach the halfway point in something.

“When we reach a midpoint, sometimes we slump, but other times we jump. A mental siren alerts us that we’ve squandered half of our time. That injects a healthy dose of stress – uh oh, we’re running out of time! – that revives our motivation and reshapes our strategy,” Pink writes.

The idea of using the midpoint to review and regroup will be familiar to most people who have played or watched sports – how often have you been in or seen a team that’s trailing at half time come out of the locker room and perform much better in the second half?

“Halftimes in sports represent another kind of midpoint – a specific moment in time when activity stops and teams formally reassess and recalibrate. But sports halftimes differ from life, or even project midpoints on one important dimension,” says Pink.

“At this midpoint, the trailing team confronts harsh mathematical reality. The other team has more points. That means only matching them in the second half will guarantee a loss. The team that’s behind must now not only outscore its opponent, it must also outscore the opposition by the amount it’s trailing.”

As an example of using the halftime break in sports, Pink recounts the story of the 1982 NCAA (US college basketball) championship game between the North Carolina Tar Heels and the Georgetown Hoyas.

After a tight first half, the Patrick Ewing-led Hoyas led by a single point.

“A team ahead at halftime – in any sport – is more likely than its opponent to win the game. This has little to do with the limits of personal motivation and everything to do with the heartlessness of probability,” Pink notes.

And college basketball was no exception. Thirty-four of the previous forty-three teams who were ahead at half-time in the championship game ultimately went on to win. Similarly, throughout the 1982 season Georgetown had gone 26-1 in games where it held a halftime lead.

However, North Carolina came out of the break fired up, and quickly took the lead back. The two teams went back-and-forth throughout the second half, before Michael Jordan hit a sixteen-foot jump shot in the final seconds that would ultimately win the championship for the Tar Heels.

The 1982 NCAA championship is an example of when motivation can overcome mathematics and probability.

Pink directs the reader towards a paper from 2011, published by Jonah Berger and Devin Pope, that investigates whether losing (specifically at half time) can lead to winning. The pair analysed over 18,000 NBA games across 15 years.

As expected, teams that were winning at halftime went on to win more games than the teams that were trailing. For example, being ahead by six points at halftime gave a team an 80% chance of still being ahead when the final buzzer sounded.

“However, Berger and Pope detected an exception to the rule: Teams that were behind by just one point were more likely to win… Being down by one at halftime was more advantageous that being up by one,” Pink explained.

Berger and Pope found a similar trend when they examined over 40,000 games of college basketball, leading them to conclude that “merely telling people they were slightly behind an opponent led them to exert more effort”.

After reading this, I was immediately curious to see if the same trend occurred in the AFL.

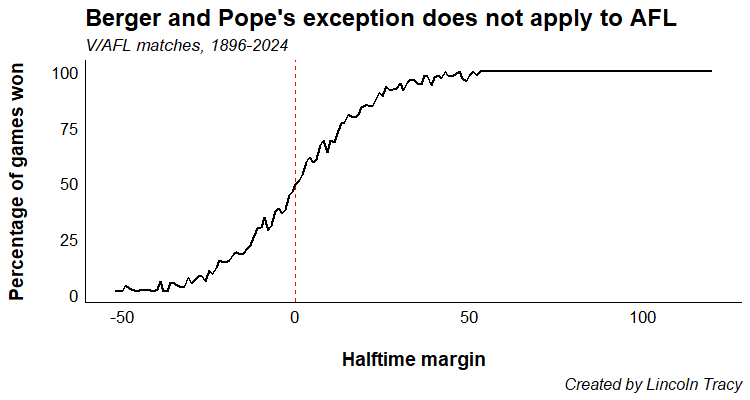

But as we can see from the figure below, it doesn’t.

While the percentage of games won by the time trailing at halftime increases the closer the margin gets to zero – from 14.7% for a team down by 20 points to 46.3% for teams trailing by a single point – teams that are winning at halftime are always more likely to win than teams that are trailing.

At least we’ll always have John Kennedy Snr’s famous halftime speech in the 1975 VFL final between Hawthorn and North Melbourne.

The timeframe of this stat is limited based on what data are freely/easily available and/or accessible. Please don’t hesitate to contact me if you spot any errors in what I have presented.